A healthier transition: Optimizing DCAB for dairy cow performance

The transition period is the most crucial phase in the production cycle of dairy cows. During this period, the cow recovers from the previous lactation, allowing the udder tissue to recover. At the same time, the calf grows rapidly and colostrum is produced. This determines the success of the start of the calf's rearing period and for the cow, the success of the next lactation. Unfortunately, this is also the period where cows have a high risk of developing metabolic and infectious diseases. Around 30 to 50% of cows develop a metabolic or infectious disease at this stage. But with the right advice about optimising the dry period, you can help dairy farmers reduce these risks. We can help you get the right knowledge and resources.

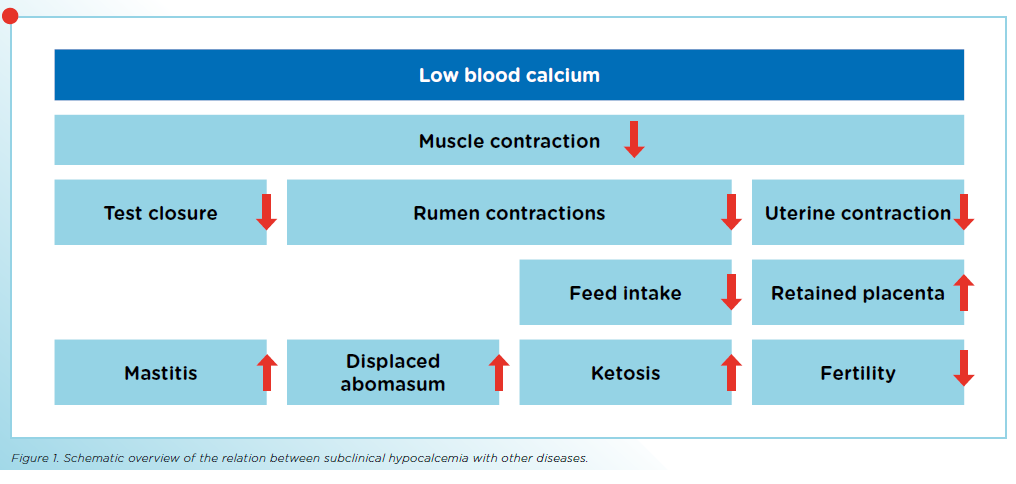

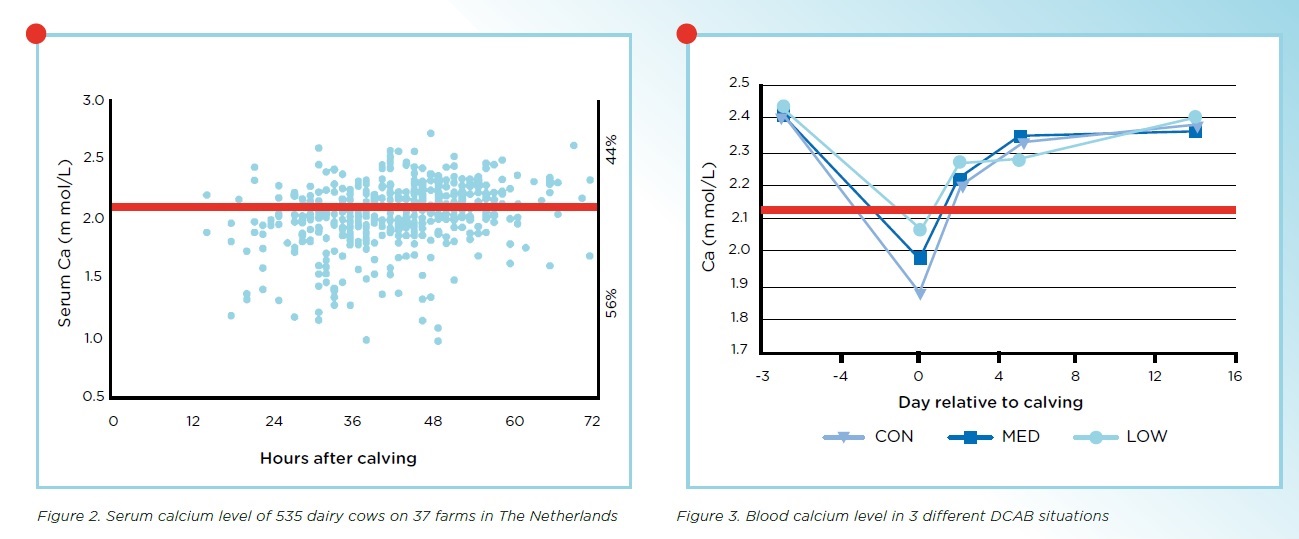

Several studies show that 40 to 80% of all older dairy cows have subclinical milk fever (subclinical hypocalcemia, or SCHC) in the first 48 hours after calving. This often goes unrecognised due to a lack of clinical signs. The low blood calcium level affects smooth muscle contractions which have a major impact on the health and performance of dairy cows (see Figure 1). Research conducted in the Netherlands on a large number of dairy farms also showed that on average 66.7% of dairy cows from second lactation developed subclinical milk fever (serum Ca concentration <2.13 mmol/L see also Figure 2).

Direct financial impact of sub-optimal transition

Without proper prevention, the financial impact of SCHC on farms can soon escalate. Based on a projected incidence of 66.7% and an average treatment cost of €113, the total cost for a farm with 100 calvings per year is more than €7,500. Because low blood calcium reduces muscle contractions (Figure 1), the disease puts cows at increased risk of developing secondary conditions such as metritis, retained placenta and displaced abomasum. In this frequently occurring scenario, the farmer is left with spiralling costs for treatment, which can amount to about €12,000 per 100 calvings, due to these secondary effects. All the more reason to adopt effective measures to prevent cows from getting SCHC.

Effective transition management

Through good transition management, a farmer can significantly reduce the risk of milk fever and SCHC. It's important of course, that the farmer has good, overall farm management, with cows starting the dry period and entering lactation with the right body condition score and an appropriate feed ration.

One tool you can use to improve the health of the cows during the transition period is management of the ration's dietary cation anion balance (DCAB). With a correct DCAB strategy, you can keep the calcium metabolism in the cow active so it meets the strongly increased calcium requirement immediately after calving.

Anionic salts as an almost ideal solution

One DCAB strategy is to feed a low-calcium ration or to feed products that inhibit calcium absorption. Well-known examples include feeding rumen-protected rice bran or zeolites. Besides being less effective, these methods often have other negative side effects. For instance, zeolite not only binds calcium but also other macro-minerals such as magnesium.

The use of anionic salts to reduce DCAB in the ration is now a widely known strategy. Lowering the DCAB by -200 meq per kg of dry matter produces a significant reduction in SCHC incidence. The fact that anionic salts' strong smell and taste makes them unpalatable has long been a counter argument for their use. However, you have the option of using different coated variants, which ensure that anionic salts don't affect the ration's palatability and in turn, lead to reduced dry matter intake.

The best strategy, but only for the perfectly managed farm

The most effective strategy to prevent health problems during the transition period is not only to lower DCAD, but to feed a negative dietary cation anion difference (DCAD), acidifying the urine. Figure 3 shows the blood calcium levels of three differently fed groups of cows. The DCAD in these rations was 220 in the CON group, 0 in the MED group and -190 in the LOW group. Lowering the DCAD to negative values lowers the blood pH of the cow, thereby also lowering the urine pH. This acidification increases the availability of calcium in the blood by improving the absorption of calcium in the gut and increasing the calcium release from the bones . This strategy also increases the excretion of calcium in the urine and hence requires extra calcium to be fed in the ration.

Despite the fact that a dry cow ration with a negative DCAD gives the best results, we recommend this only for customers with top-notch farm management. This is because the farmer has to ensure that the urine pH stays above 5,5 - 6. When the DCAD is too negative, the blood pH will become so low that the cow's health will be at risk. So precise feeding and good monitoring is essential. However, this can be planned, avoiding unplanned work due to diseases after calving.

Read the latest version of the Koudijs newsletter!

Read hereAbout the author

Thijs Hunink

Specialist Ruminants

Do you have any questions or would you like more information? Get in touch with Thijs.