Feeding the modern day gilt – a practical approach

Each sow farm has two completely different groups of animals in its herd: multiparous sows and gilts. With modern genetics, the difference between these groups is even greater. In previous editions of this newsletter, we focused on a practical approach to the modern gestating and lactating sow. This sow is highly capable of mobilising reserves, making her in fact, a perfect “battery”. However, this battery needs to have great capacity and durability. But how do you create such a battery? It all starts with gilt development.

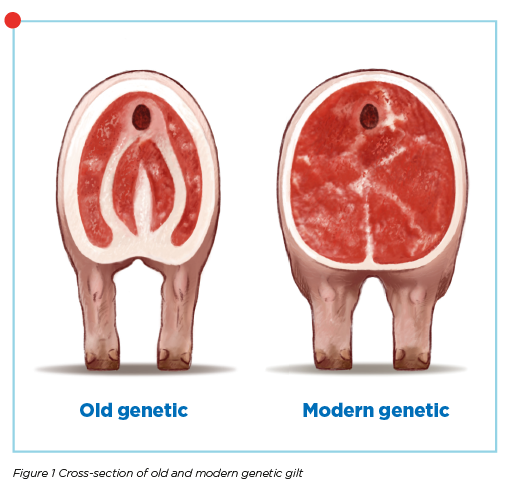

Gilts are heavier, not fatter

Modern sow genetics are completely different from the genetics of 10 years ago, especially in terms of protein and fat deposition. As shown in figure 1, the modern gilt is leaner compared to older genetics. A lean gilt means fewer bodily reserves, which is like a battery with less than full capacity. Gilts therefore have to grow to a certain minimum body weight to have minimum fat mass, meaning they will be heavier. So nowadays, we have to look at gilts from a different perspective: gilts are heavier, not fatter.

Puberty: Extra growth means extra feed

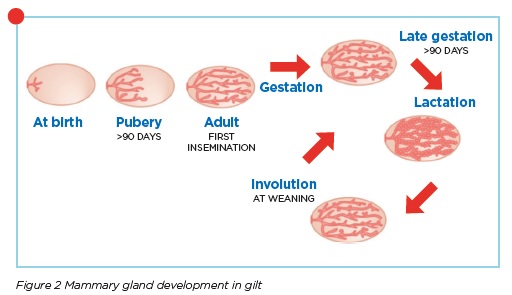

Gilts enter puberty at 90 days of age. In this phase, reproductive organs start to develop: mammary glands (see figure 2), uterus and ovaries. As a result, gilts need sufficient feed to support this development. Restricted feeding in this phase, often used to prevent too heavy gilts, results in underdeveloped reproductive organs, like smaller vulvas and mammary glands. Research shows that mammary gland development during puberty is strongly influenced by daily energy intake. Depending on diets, feeding systems and housing, we recommend avoiding restricted feeding as much as possible and avoiding variation in the weights of your gilts.

Continue charging the battery after first insemination

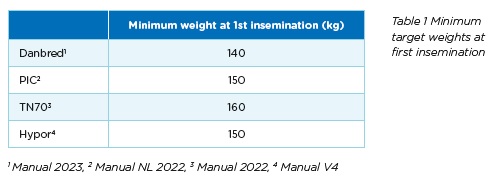

Stating the obvious, the timing of the first insemination is essential to developing a gilt with high productive capacity and durability. Because gilts are leaner, we have to focus more on minimum body weight. Our principle is to inseminate each gilt at minimum weight and in her second or third heat. In practice, this means that average weights at first insemination have to be ±10kg heavier than recommended in genetic manuals (see table 1). By doing so, we prevent some gilts being inseminated below minimum weight. For example, if a farm inseminates at an average of 160kg, keep in mind that 5-10% is below the target weight. Target weights should be seen as minimum for all gilts, not as an average. After insemination, a gilt is not mature and still needs to grow in maternal body weight (excluding uterine content) in her first parity. Remember as well that a gilt needs to grow about 70kg during the gestation period. This means she has to continue to grow at more than 600g per day in weight.

Optimal battery capacity to minimise second litter syndrome

It's all right for first parity sows to be in a negative energy balance during the lactation period. However, the first parity sow is much more on the verge of having a too negative energy balance. The lactation period places an extreme metabolic demand on first parity sows. They have a high litter gain, but are still growing and have lower feed intake capacity compared to multiparous sows. This can result in too much weight loss during lactation. The maternal body weight loss should not be to extreme, with a maximum 10-12% for first parity sows.

Too much weight loss can result in a prolonged weaning-to-estrus interval, reduced litter size or farrowing rates in second parity sows: the second litter syndrome. There are two options to prevent second litter syndrome: 1) limit weight loss in the lactation period, 2) start with good body weights (good battery), not only at insemination but also at farrowing.

Because the production level of gilts’ lactation period is already so high, you have to start with a “more solid battery that can be charged” at insemination.

Practical actions you need to take into account:

- Be careful with restricted feeding in the puberty phase and use an adjusted feeding schedule during gestation.

- Invest in a weighing scale and weigh gilts at 3 moments: 1) at insemination, 2) just before farrowing, 3) at weaning.

What nutritional considerations do you need to take into account:

To obtain optimal gilt development and sow longevity, (feed) management and feed composition go hand in hand. Some nutritional considerations are listed below:

- Use multiphase gilt rearing feed programme from 25kg.

-

- Adapted protein-to-energy ratio in feeds with focus on fat deposition (different to finisher feeds).

- Use different fibre fractions for rest, satiety and preparation for gestation phase

- Levels of macro minerals (calcium and phosphorus) for gilt longevity are significantly different than for finishers.

- Match feeds and feeding schedule to genetics.

- Feeding the gilt, to create a high capacity and durable battery needs to be supported. Feeding gilts and sows with the right sources and amounts of vitamins and trace elements is very important to creating a high-capacity and durable battery. Koudijs has revised these recommendations for the modern gilt and sow.

Feeding choices in gilt development determine the capacity and durability of the future sow. We have experienced in practice that our way of combining your knowledge and experience with ours leads to very predictable and effective results, and is high appreciated by our customers. This article is part of the Koudijs’ sow vision. For more information, please contact us.

About the author

Suzanne Hendrikx

Swine Specialist